Let the fun begin! There’s nothing like starting chapter 1. In any great work, Chapter 1 is where we get the feel for the tone and atmosphere of the book. We get to learn who is speaking and how the story will be told, so without further ado, let’s get to it.

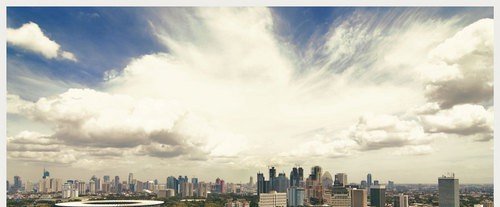

The year is 1801 and the month is November, and since we want to get into the world of the novel as much as we can, let’s recount some things that have happened this year. In the United States, Thomas Jefferson defeats John Adams for the presidency and becomes the third United States president. In Haiti, Francois Dominique Toussaint L’Ouverture, a former slave turned into respected general drafts a separatist constitution and as a result faces the wrath of Napoleon Bonaparte and his 40,000 troops. Toussaint will eventually be captured, shipped off to France and die in imprisonment. In Hungary, Ludwig Van Beethoven finishes composing the Moonlight Sonata.

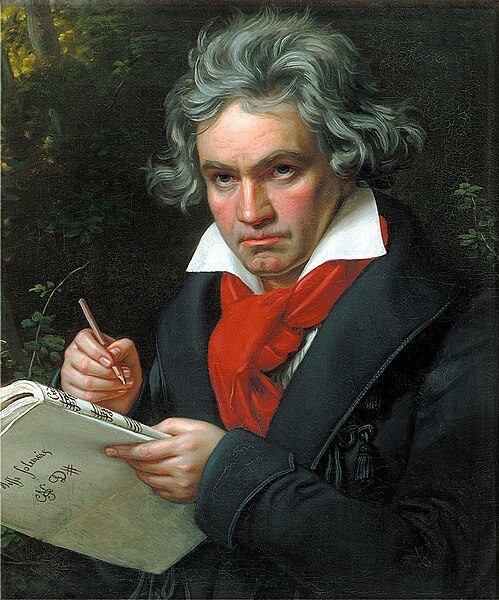

Painting by Joseph Karl Stieler, 1819 or 1820

We will begin with a summary of the chapter and then get into analyzing some significant details of this opening in my next post. Our narrator is Mr. Lockwood (we never learn his first name throughout the novel). The chapter begins with Lockwood relating his first visit to his landlord Mr. Heathcliff (we never learn his first name throughout the novel). Lockwood tells of how beautiful and solitary his new area of residence is and describes it as “a perfect misanthropist’s Heaven” (1). He then begins to recount how similar he and Heathcliff are and describes Heathcliff as a “capital fellow” (1), despite receiving a rather less than pleasant welcome from Heathcliff. Lockwood meets Heathcliff at Wuthering Heights, which is about four miles away from where he will be a tenant at Thrushcross Grange.

Upon entering the premises, Lockwood encounters Joseph, Heathcliff’s elderly servant who is as equally unwelcoming as Heathcliff. Lockwood notices a carving above the principal door stating “1500” and “Hareton Earnshaw” and thinks about asking Heathcliff to tell him about the premises, but due to Heathcliff’s attitude changes his mind. Upon entering the family-sitting room, Lockwood describes his surroundings and sees dogs and a “swarm of squealing puppies” (3) and begins upon a detailed description of Heathcliff:

He is a dark-skinned gypsy in aspect, in dress and manners a gentleman – that is, as much a gentleman as many a country squire: rather slovenly, perhaps, yet not looking amiss with his negligence, because he has an erect and handsome figure – and rather morose – possibly some people might suspect him of a degree of under-bred pride. (Bronte 3-4).

Lockwood’s somewhat superior description of Heathcliff is followed by his explanation of Heathcliff’s personality and reserve. In this very important part of the chapter, Lockwood continues to explain Heathclif’s personality, assumes it to be similar to his own and then internally shares a story of one of his past heartbreaks. We will explore this in depth in the next section.

After taking a seat, one of Heathcliff’s dogs approaches Lockwood and growls violently at him after he attempts to pet her. Heathcliff tells Lockwood to leave the dogs alone, and calls out to Joseph, and as Joseph gives an indication of not coming, leaves to go find him in a cellar below. The dog and a pair of sheep dogs begin to surround Lockwood, as he attempts to sit still while for some reason making faces at the dogs. Irritated by his behavior, one of the dogs pounces at his knees and Lockwood flings her back and tries to put a table between himself and the dogs. This aggravates all the dogs, and they surround him while he attempts to defend himself with a poker. While Heathcliff and Joseph ascend back from the cellar in an unhurried manner, Lockwood is saved by Zillah, Heathcliff’s housekeeper, who chases the dogs away with a frying pan and an authoritative manner.

Heathcliff shows little sympathy and blames the indignant Lockwood for the dogs’ outburst, but a little later allows a grin to pass over his face and calms the situation by offering Lockwood a little wine and starting a conversation about the advantages and disadvantages of residing in Thrushcross Grange. The chapter ends with Lockwood complimenting Heathcliff’s intelligence and remarking that he will visit Heathcliff again the next day, despite Heathcliff’s lack of interest in a repeat meeting.

Analysis and Questions

The novel begins with Lockwood and his estimations of the area he is in and the people he encounters. The story is told from his perspective and we are free to make our own estimations based on what he describes to us. I enjoyed this beginning very much because what Lockwood tells us seems to be at a discord from what actually occurs as he describes it. He comments on the beauty of Wuthering Heights and his disbelief that he “could have fixed on a situation so completely removed from the stir of society. A perfect misanthropist’s Heaven” (1). Judging by this, Lockwood is telling us that he is someone who prefers solitude and dislikes the company of people.

He then continues to say that “Mr. Heathcliff and I are such a suitable pair to divide the desolation between us. A capital fellow! He little imagined how my heart warmed towards him when I beheld his black eyes withdraw so suspiciously under their brows, as I rode up, and when his fingers sheltered themselves, with a jealous resolution, still further in his waistcoat” (1). Notice the difference here between what is said and what occurs. Lockwood describes himself as basically Heathcliff’s spirit animal and talks of how his heart warms at seeing him, while Heathcliff does everything in his power to squirm away from what we imagine is a very unpleasant encounter for him. Several questions arise from this.

Can we trust anything Lockwood tells us as reliable information? He clearly doesn’t seem to get that Heathcliff and him seem to be nothing alike.

Does that really matter? Though Lockwood might misinterpret what is happening, does it really effect what is factually happening in the story?

What function does Lockwood serve as the narrator of this beginning? What tone does he set? Why is Lockwood telling this story?

With these questions in mind, let’s find out more about Lockwood. We can determine a lot about him, by seeing how he speaks to Heathcliff when introducing himself. Lockwood begins, “I do myself the honour of calling as soon as possible after my arrival, to express the hope that I have not inconvenienced you by my perseverance in soliciting the occupation of Thrushcross Grange: I heard, yesterday, you had some thoughts-” (1), Lockwood’s flowery recitation indicates higher breeding and class, but also a lack of directness and firmness and is rudely interrupted by Heathcliff’s curt response, “‘Thrushcross Grange is my own sir’ he interrupted wincing, ‘I should not allow any one to inconvenience me, if I could hinder it-walk in!'” (1) Their first lines of dialogue clearly indicate that Lockwood and Heathcliff are as different as night and day. Heathcliff shows himself to have no time for lengthy and polite introductions and makes it clear that he has no interests in sharing his thoughts with Lockwood or anyone else for that matter. Even Lockwood notices this and remarks that Heathcliff’s “‘walk in’ was uttered with closed teeth and expressed the sentiment, ‘Go to the Deuce!'”

Does this interaction establish Lockwood as a device to illustrate Heathcliff with more detail?

Do we naturally need a goofy Lockwood to bring out the grizzly and grumpy Heathcliff as to establish him better?

Despite the gruff invitation, Lockwood cannot resist visiting Heathcliff and for his reason states that he “felt interested in a man who seemed more exaggeratedly reserved than [himself]” (2). The comedic presence of Lockwood also sheds more light onto Heathcliff’s elderly servant Joseph, whom upon meeting, Lockwood describes as “looking, meantime, in my face so sourly that I charitably conjectured he must have need of divine aid to digest his dinner” (2). Lockwood clearly seems to be out of place and unwelcome in this setting, yet continues to maintain that he has many commonalities with Heathcliff. Lockwood confesses that he “know[s], by instinct, his [Heathcliff’s] reserve springs from an aversion to showy displays of feeling – to manifestations of mutual kindliness. He’ll love and hate, equally under cover, and esteem it a species of impertinence to be loved and hated again” (2). Later in the novel, we’ll discover that Heathcliff has no problems loving and especially hating in the open and not undercover as Lockwood presumes, and even Lockwood recovers from this romantic description and admits that he “bestow[s] my own attributes over-liberally on him” (2).

Lockwood reveals more about himself by recalling a story of him on a vacation at a sea-coast and falling in love with a woman and not telling her that he was in love with her. When she understood that he was in love, she returned a sweet look to him, only for him to “shrink icily” into himself and become colder, until his poor crush started to doubt what she had sensed and asked her mother to leave the vacation spot. This story gives us an excellent portrait of Lockwood and further illustrates how different he and Heathcliff are, because Heathcliff has so far not displayed any timidity or fear.

The chapter continues to be comically entertaining through Lockwood’s interactions with this environment. He is attacked by Heathcliff’s dogs, is inefficient in defending himself and contrasts poorly even with Heathcliff’s elder female servant who ends up rescuing Lockwood with a frying pan and a loud voice. Heathcliff finally takes pity on Lockwood and offers him a glass of wine and some laconic conversation. This encourages Lockwood to repeat his visit on the next day and leads him to the conclusion that it is “remarkable how sociable I feel myself compared with him” (6).

This brings us to the conclusion of chapter 1. We have already posed some questions through this reading. What other questions pop up as we think about this chapter? Please leave your comments and questions, and let’s head on to chapter 2!