Imagine yourself in an empty room, with nothing in it, except a window and a desk. You go to the window and see nothing apart from a small ray of sunshine and a brick wall of another building exactly like yours. You go to your desk and open a drawer. Inside you see a stash of papers, and you examine their contents. You see nothing but legal jargon and realize that five of those papers are identical in every word. The sense of emptiness overwhelms you and you decide to go outside. On your way down, you notice rooms that are like yours, with someone sitting at a desk, writing the contents of one paper on another. You finally make it outside and have difficulty distinguishing one building from another and as far as you can see, the rows of the same structure depart for several blocks. You listen to a conversation and it is similar to a conversation you heard yesterday and the day before.

Prefer Not To

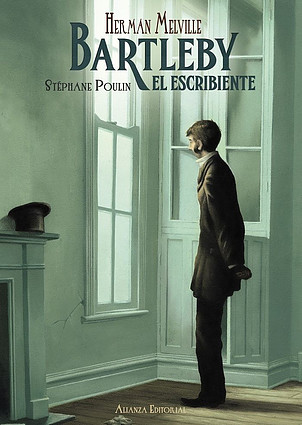

The sense of emptiness in Herman Melville’s Bartleby is frighteningly apparent in every description of the office and work duty involved. The reaction and decline of Bartleby appears more natural, as the setting of a fast paced, economically booming Wall Street makes itself perceptible. This work is an allegory for corporate discontent. Bartleby is a sensitive, timid soul who only shows firmness in his utter abandonment of any sort of occupation. It is pleasantly convenient that the narrator is also a meek man who tends to avoid conflict and rather adjusts to his environment and the people within it. This capability allows him to survive the travails of a soulless working establishment, where everyone is expendable and sympathy lasts a short time. Bartleby drowns his apprehensions in diligent and precise work, until that can no longer emotionally uphold him. His “preference not to” do little tasks or errands, nor later on to change professions, signifies his lack of enthusiasm and excitement for any task in an empty environment and life. The descriptions of Bartleby become linked to that of a phantom or a ghost, further delineating him as an outsider, or someone not of this world.

Bartleby’s inability to cope and adapt to this life doesn’t, at a second glance, seem overly unnatural. Rather, the state of Turkey and Nippers comes into question, as their strange parallelism comes into view. Their temper switches back and forth between them as morning turns into afternoon. Their temperaments and eccentricities are unsympathetic and repellent. Their behavior seems to be a result of their coping with their environment and seems in that sense as a bigger negative than the outcome of Bartleby’s conflicted and tragic personal battle.

It is unfortunate that poor Bartleby’s setting transforms from a closed office to an actual jail. This sad shift illustrates that corporate and professional captivity does not differ much from actual captivity and contains the same sort of hopeless emptiness as an empty room you are not allowed to leave.

Author: Kristap Baltin – Kristapbaltin.com

A good edition of Bartleby the Scrivener sold here.