Analysis of Raymond Carver’s Careful

There are times when we are unsure of our final decision. We have pleasant memories of a fading past and seek to wade in an uncertain river for a second time. A hesitation arises and lingers in the bad recollections, which drives us to a final test. This examination reveals the initial instinct and reconfirms the alarming intuition driving us farther away in the opposite direction. This might be the reason Inez visits hapless Lloyd in the hour of his ailment and performs a careful operation intended to revive his hearing. Her success might lead to his redemption or further thrust him into imminent downfall, confirming her original pronouncement. It is possible, that Inez simply stops by to check on her unfortunate husband out of concern and pity. Perhaps she has not even considered a possible reunion and does not intend to perform any such test as will reveal the worthiness of her ill-fated husband. Raymond Carver’s story Careful seems to suggest otherwise. Lloyd’s disease is emotional, not physical. Therefore, Inez’s operation is not a surgery, but rather an attempt at revival. There is a pattern in Lloyd’s thoughts and actions, a pattern of weakness and failure leading him to a certain outcome, even when assisted by the caring hands of Inez, who seeks to test and examine her husband for even the slimmest chance of salvation.

There are only small hints of Lloyd’s normalcy and competence as a man/husband prior and during his time with Inez. When having doughnuts and champagne for breakfast he remembers, “some years back, when he would have laughed at having a breakfast like this. Time was when he would have considered this a mildly crazy thing to do, something to tell friends about” (Carver 265). Now, his own state does not seem strange or unusual to him. This detail does not matter to him in one way or the other. His attitude is nonchalant and any judgment against his behavior solicits a careless “So what?” Lloyd’s other recollection takes place at the municipal pool. He compares the difficulty of curing his ailment with the ease of clearing his ears in the past:

But back then it’d be easy to clear the water out. All he had to do was fill his lungs with air, close his mouth, and clamp down on his nose. Then he’d blow out his cheeks and force air into his head. His ears would pop, and for a few seconds he’d have the pleasant sensation of water running out of his head and dripping onto his shoulders (carver 268).

This comparison is very significant in helping to understand why Inez dismisses Lloyd in the present, yet accepted him in the past .Not long ago; Lloyd cured his problem with ease, because he did not essentially have a problem. It was a little bit of water clogged in his ear, similar to a little bit of wax stuck in his ear presently. Lloyd does not have a problem with hearing, but rather a problem with listening. Inez takes great pains in helping Lloyd and undertakes a laborious process, comparable to coddling a sick child, yet sometime in an immediate past all he had to do was fill his lungs with air and clamp down on his nose.

Though lacking in sound judgment, Lloyd senses his inadequacy and understands his need for redemption. He knows that he should not be an alcoholic, but attempts to cure his addiction by drinking champagne, a less potent alcohol. He thinks that he will better himself by being alone and instead deteriorates his mental state through isolation and carelessness. His incapacity drives him to a series of mental mistakes, but even these do not rob him from the realization of his wife’s importance. Sensing his wife’s presence, Lloyd “knew it was Inez and somehow he knew the visit was an important one” (Carver 266). Lloyd understands that his wife’s judgment will either save or doom him, and that she is his only hope of deliverance. He therefore hides his bottle of champagne and justifies himself being dressed in pajamas at 11 A.M. It is almost likely that he is lying about his ear condition to excuse his shoddy appearance and bad state. This seems even more possible with the consideration that later, when his ear is unclogged, he is still unable to hear Inez.

Inez shifts from intense moments of action to reflective meditation. She looks for solutions and seeks to find different tools for her purposes. The times between are spent in smoking cigarettes and gazing at Lloyd and contemplating her next step. Similar to a physician, she gently tests different objects and tenderly inserts them into Lloyd’s ears, poking for any sign of a positive response. The ineffectiveness of her preliminary cures does not reflect badly on her, but rather on the stubbornness of Lloyd and his condition. At one point, “He turned his head to the side and let it hang down. He looked at the things in the room from this new perspective. But it wasn’t any different from the old way of looking, except that everything was on its side” (Carver 273). This is a perfect example of Lloyd’s ineffectiveness and for a lack of better word, perspective. After a while, the fluid flows from his ear and restores his hearing, yet no change has occurred internally within Lloyd. Whether or not he has wax clogged in his ear, everything remains the same for him. His room, situation, and mental state remain unalterable and hopeless. His endless addiction and justification lead him astray in every turn and he is tragically unable to respond to his wife, even with something so simple as sincere gratitude.

Instead of realizing his true problems, Lloyd comes up with dim ideas of sleeping on his back instead of his side. Lloyd’s emotional turmoil is too heavy for him to bear, so he displaces it into a petty physical ailment. Meanwhile, Inez observes every reaction and response. Throughout the story, her pleas to talk to Lloyd are ignored and dismissed with incoherent and foolish replies. This is more so significant after the cure of his ailment and the return of his ability to hear clearly. On her way out, Lloyd asks, “Inez, where do you have to go?” “I told you,” she said and made ready to leave” (Carver 275). Further on Lloyd’s real condition becomes even clearer:

But at the door she turned and said something else to him. He didn’t listen. He didn’t want to. He watched her lips move until she’d said what she had to say. When she’d finished, she said, “Goodbye.” (Carver 275).

From the very beginning, Lloyd does not want to listen, for he is afraid of what he will hear. His physical condition solely reveals his inner malfunction. For Inez it was necessary to heal the physical half in order to understand Lloyd’s true mental state. When she finishes the task, her realization is instant and immediate. She understands the futility, but still shows enough care to talk to the old woman living below Lloyd. Ironically, Lloyd listens with great care, as Inez parts with the old woman and drives away.

The operation is a failure and Lloyd’s earlier sentiments might very well become a reality. “If this doesn’t work, I’ll find a gun and shoot myself. I’m serious. That’s what I feel like doing, anyway” (Carver 273). Unfortunately, for Lloyd it does not work, and though it is unlikely he will find a gun, it foreseeable that his end will be before long and more tragically dragged out than a swift gun shot. Inez’s comparable sentiments illustrate a more positive image, “Anyway, we need to try something. We’ll try this first. If it doesn’t work, we’ll try something else. That’s life, isn’t it?” (Carver 269). Inez’s charming query falls on deaf ears and while she can try something else with a sensible outlook, it is a shame that such a good operator should fail because of such a poor patient.

Author: Kristap Baltin – kristapbaltin.com

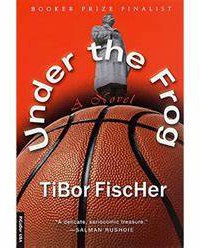

The Tears of Episodic Laughter

The Tears of Episodic Laughter