Introduction:

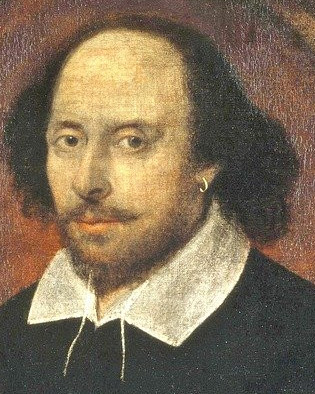

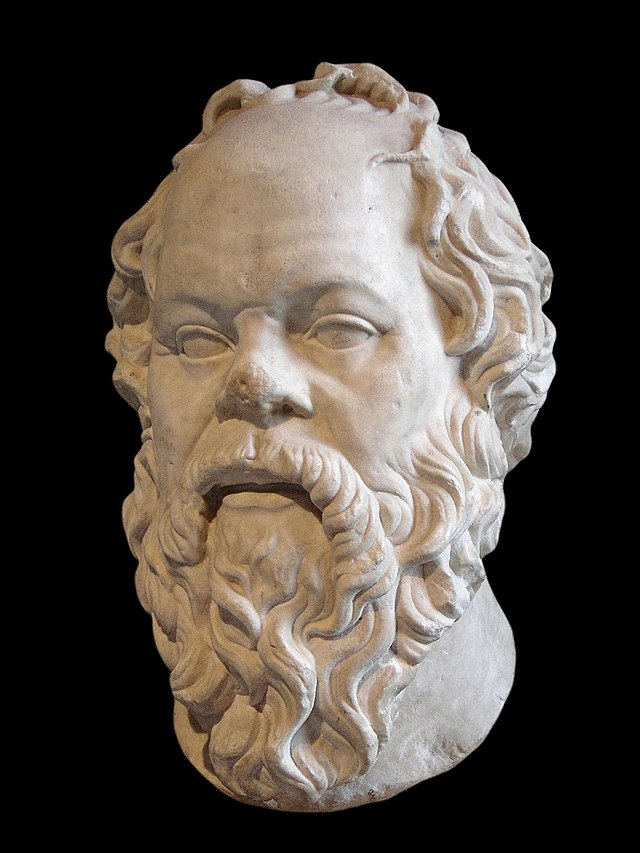

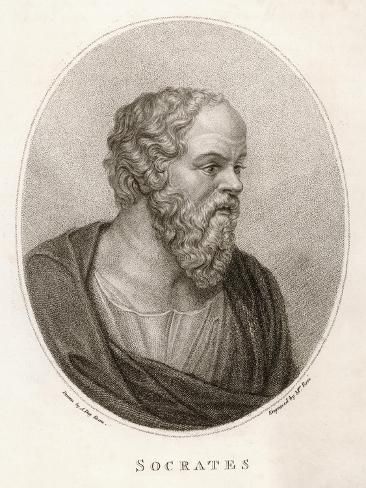

Plato’s Apology, rightfully considered to be one of the founding philosophical works of western civilization, is about the trial of Socrates and his oral defense against his accusers.

The dialogue begins in the middle of Socrate’s trial, before we even know what he is accused of. It starts off with him directly addressing the jury of 500 Athenians in attendance of his trial. He begins by addressing what he calls the old charges leveled against him, and not the ones by his official 3 accusers of Anytus, Meletus and Lycon. Those old charges consist of “telling of one Socrates, a wise man, who speculated about the heaven above, and searched into the earth beneath, and made the worse appear the better cause” (Plato, Apology, 200).

Why are those charges so bad?

That Socrates “speculate[s] about the heaven above, and searche[s] into the earth beneath” implies that he may be an atheist, and while this in itself was not illegal, Athens was a deeply religious society and a lack of proper respect for the gods showed an absence of respect for Athenian traditions and culture.

The second part of this accusation – “ma[king] the worse appear [to be] the better cause” is akin to accusing Socrates of being a sophist.

What is a sophist? A sophist is someone who is skilled at arguing about something that is untrue, but making it sound correct. This is an accusation that many skilled rhetoricians and philosophers were accused of, as their skill in debate and argument could often be used in a damaging manner by arguing that something that is a net negative in society is actually beneficial and good. We have many modern examples of this in society today. In media, persuasive techniques are often used to shape public opinion and influence individuals. This can involve selectively presenting information, using emotional appeals, or distorting facts to manipulate the audience’s perception and sway their opinions.

Socrates’ defense to these accusations

Socrates tells the story of his friend Chaerephon going to Delphi and asking the oracle to tell him if there is anyone wiser than Socrates. The oracle tells Chaerephon that there is no man wiser than Socrates. Seeing this as a riddle, and not believing the words of the oracle, Socrates goes about the task of finding someone who is wiser than he is. His strategy for this is to find people considered to be wise by the Athenian community and asking them questions. As he begins to question the people he encounters, he notices that they opine on subjects that they have no knowledge of, and truthfully tells them that they are not wise, which as a result makes these people with good reputations hate Socrates.

Oracle of Delphi

Oracle of Delphi

Socrates’ impression after talking to these individuals is best presented in this summary “although I do not suppose that either of us knows anything really beautiful and good, I am better off than he is,- for he knows nothing, and thinks that he knows; I neither know nor think that I know” (Plato, Apology, 202). In short, Socrates does not pretend to any knowledge beyond him and therefore seeks what he does not know, while other hold pretensions of wisdom without being able to back it up with knowledge.

Socrates takes it as a holy mission to figure out what he considers to be a riddle by the oracle, and in his quest questions politicians, poets and artisans, and while he sees that the poets and artisans are talented and naturally able, they believe that the wisdom they have in their talent transcends to wisdom in other matters, which isn’t true. As you can see, the wide range of important and highly regarded people in Athens feeling like fools after their conversation with Socrates is a bad omen for him, as he is making enemies of the most powerful and influential people in his community.

The Moral Lesson of this Defense

The speech Socrates makes after relating the story of his questioning of the people considered to be wise in his community is key to understanding the moral he wished his audience to perceive:

This inquisition has led to my having many enemies of the worst and most dangerous kind, and has given occasion also to many calumnies. And I am called wise, for my hearers always imagine that I myself possess the wisdom which I find wanting in others: but the truth is, O men of Athens, that God only is wise; and by his answer he intends to show that the wisdom of men is worth little or nothing; he is not speaking of Socrates, he is only using my name by way of illustration, as if he said, ‘He, O men, is the wisest, who, like Socrates, knows that his wisdom is in truth worth nothing’ (Apology 202-203).

This quote reaffirms how dangerous the enemies he has made are, but also effectively disputes the charge of atheism laid upon him. His claims that only “God is wise” and that the “wisdom of men is worth little or nothing” demonstrates his piety and his belief in a higher power. He does not take being called the wisest as a compliment or as something to indulge his vanity, but rather as a demonstration that mankind is vain and pretentious. That people do not spend enough time seeking truth and wisdom, and lie about how much they know. His mission is to reaffirm God’s message and he tirelessly and to the detriment of his safety and wealth continues his mission of questioning his society in “vindication of the oracle” and God’s message.

The Charge of Corrupting the Youth

This charge is brought upon Socrates by Meletus, Anytus and Lycon, as the society of Athens is afraid that Socrates’ influence upon the young will lead them to question the wisdom and integrity of those whom Socrates has made seem foolish through his questioning. This is a threat as the people who are questioned are observed by the youth, who in turn imitate Socrates and proceed to examine others. As the youth is the future of Athens, it is understandable, how much of a threat Socrates may pose to Athenian understanding and culture. Socrates points out that instead of being angry with themselves, the victims of his questioning turn their anger towards him.

On Death and the Fear of Death

Socrates does not see the accusations against him as the real reason behind his prosecution. He is aware that his work of questioning the highly reputed members of Athenian society has gained him powerful enemies, and that as a result he will most likely be convicted of being guilty and put to death, as it is goes against his values to stop questioning others and searching for the truth. It is at this point that he engages in a poignant speech that culminates his defense, and becomes more a contemplation of his circumstances. He explains this in the following passage:

but I know only too well how many are the enmities which I have incurred, and this is what will be my destruction if I am destroyed;—not Meletus, nor yet Anytus, but the envy and detraction of the world, which has been the death of many good men, and will probably be the death of many more; there is no danger of my being the last of them (Plato, Apology, 205)

Socrates knows that he is a revolutionary figure, that his quest for truth and his talent for revealing it makes important figures in the Athenian society uncomfortable and afraid of losing their influence. Therefore, it’s “envy and detraction of the world” that will spell his doom, as it has to other revolutionary and unique men throughout history. This is the beginning of Socrates coming to accept his fate and explaining that he has a moral imperative of continuing along on his path even if it means he will die. He knows that at this point he still has a chance to survive. If he shows contrition, he could either promise to stop his current way of life and/or accept exile to a different part of Greece. Anticipating the criticism the jury might pose to him, of being foolish for proceeding on a path of life that will lead to his untimely destruction, Socrates states that “a man who is good for anything ought not to calculate the chance of living or dying; he ought only to consider whether in doing anything he is doing right or wrong—acting the part of a good man or of a bad” (Plato, Apology, 205). Socrates is incorruptible, he will choose death over living a life incongruent with his values and morals. In his mind, men who will not, are not “good for anything.”

Comparisons with Achilles

For Socrates courage is a virtue, and Achilles is one of the foremost examples of courage and nobility. There will be a long block quote beneath this paragraph, please read it carefully, keeping in mind how much stock Socrates is placing in abiding by your values, honor and the truth of who you are and what your purpose is. When speaking of Achilles, Socrates states:

Whereas, upon your view, the heroes who fell at Troy were not good for much, and the son of Thetis above all, who altogether despised danger in comparison with disgrace; and when he was so eager to slay Hector, his goddess mother said to him, that if he avenged his companion Patroclus, and slew Hector, he would die himself—“Fate,” she said, in these or the like words, “waits for you next after Hector;” he, receiving this warning, utterly despised danger and death, and instead of fearing them, feared rather to live in dishonor, and not to avenge his friend. “Let me die forthwith,” he replies, “and be avenged of my enemy, rather than abide here by the beaked ships, a laughing-stock and a burden of the earth.” Had Achilles any thought of death and danger? For wherever a man’s place is, whether the place which he has chosen or that in which he has been placed by a commander, there he ought to remain in the hour of danger; he should not think of death or of anything but of disgrace (Plato, Apology, 205-206).

Due to his mother Thetis, a goddess, Achilles has privileged information about his future. He knows that if he goes on to slay Hector in battle, it is foretold that he will perish. When Socrates says that Achilles “despised” danger and death, it means that he is uncomfortable with them. He is a complex character who is attached to life and the glory of his own existence, but the greatness of Achilles is reflected in his amazing ability to overcome his lust for life in order to avoid dishonor. When he says “let me die forthwith and be avenged of my enemy” it means right away, without a delay. There is no hesitation in his decision to do the right thing. If he had chosen a prolonged life, it would amount to nothing more than being “a burden of the earth.” Socrates chooses this as a model for his own life. There is a divine element in his stating that “for wherever a man’s place is, whether the place which he has chosen or that in which he has been placed by a commander, there he ought to remain.” In Socrates mind the “right thing” is that which God has placed man naturally in. It is up to the man to execute God’s command and do that which is natural, difficult, yet right, rather than choose that which is an escape of duty for the sake of self-preservation. If in danger, the man should not think of death, but rather of the shame of disgrace. So it follows that if Socrates should stop his mission of questioning, it would be disgraceful and would go against God.

This painting, by Edward John Poynter aptly named “Faithful Until Death” is appropriately illustrative of Socrates’ philosophy. It shows a soldier dutifully guarding Pompeii as it is destroyed by a volcano. The duty of protecting the city and being placed there is a matter of honor and courage. You can see the chaos that is in contrast with his concerned yet calm pose within the gates of the city. There are chaos and death and people clearly trying to protect themselves, while he stoically carries on with his job despite the promise of a swift death he is more than aware of eventually coming for him.

On Death and the Fear of Death – Part II

It becomes clear through Socrates speech that he truly is not afraid of death. It is most apparent in this passage:

For the fear of death is indeed the pretence of wisdom, and not real wisdom, being a pretence of knowing the unknown; and no one knows whether death, which men in their fear apprehend to be the greatest evil, may not be the greatest good. Is not this ignorance of a disgraceful sort, the ignorance which is the conceit that a man knows what he does not know? (Plato, Apology, 206).

This observation of how people fear death flawlessly drifts into Socrates explanation of wisdom – not pretending to know something one does not know. If people do not know what happens immediately after death, it is a pretence to be afraid of it. Socrates sees no reason to avoid death, especially if it means it would lead him to disgrace and worthlessness. His wisdom allows him to not fear it, and even be curious as to what it may lead to.

The Version of Plato’s Apology I used for this Article

GREAT BOOKS OF THE WESTERN WORLD: VOLUME 7. PLATO: Robert Maynard Hutchins, Editor: Amazon.com: Books

Author: Kristap Baltin

What the Ship From Delos might have looked like.

What the Ship From Delos might have looked like.

(an artistic rendition of Petrarch’s beloved Laura)

(an artistic rendition of Petrarch’s beloved Laura)

The Tears of Episodic Laughter

The Tears of Episodic Laughter